More History of Wyoming’s Judicial System

In 1788, the newly ratified United States Constitution heralded a new form of government. In 1889, Wyoming voters ratified their own constitution, effective on July 10, 1890, the date Wyoming was admitted as a state in the union.

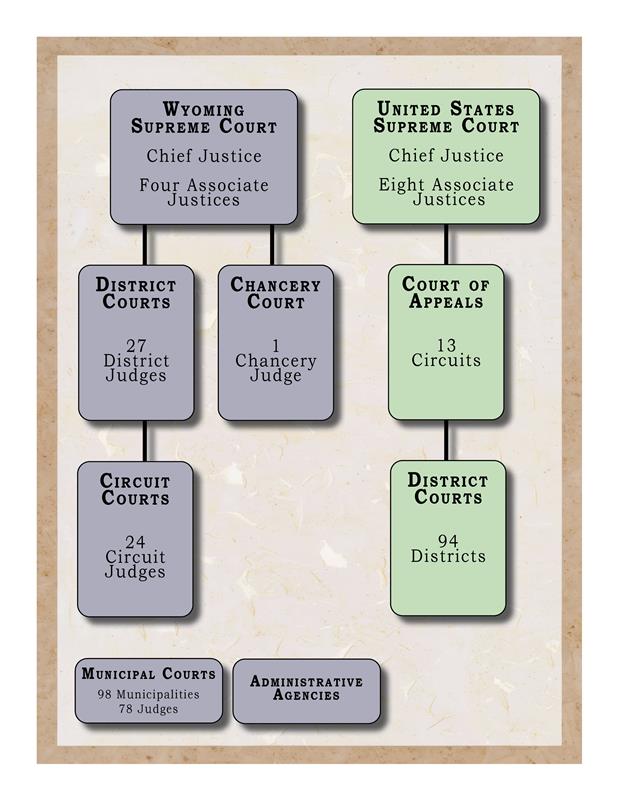

These documents, with their subsequent amendments, contain the basic principles of government and the essential rights guaranteed to each citizen of Wyoming. The Wyoming and the United States Constitutions created three separate and co-equal branches of government. Each is charged with unique duties meant to ensure that our constitutional legacy continues to be the birthright of every citizen. The Legislative Branch, based on the concept of majority rule, makes law through the passage of statutes, which are then enforced by the Executive Branch. The Judicial Branch must interpret and enunciate the meaning of the law through the adjudication of disputes. The Judicial Branch is the branch which reviews the laws as they apply to actual events in the lives of individuals. As envisioned by the founders over two hundred years ago, when the judicial system protects the rights of one, the rights of all remain secure.

Wyoming’s first courts were created in the Organic Act, which was enacted on July 25, 1868, and established the government for the Wyoming Territory. The power of the Wyoming territorial courts was established in four different types of court. The Supreme Court, which was the territory’s appellate court, consisted of three justices—a chief justice and two associate justices—who were appointed by the President of the United States. The justices served four-year terms, and could be removed from office during that term only by the president and with the consent of the senate.

President Ulysses S. Grant appointed John H. Howe as the first chief justice of the Court, and associate justices Joseph W. Fisher and John W. Kingman.

The territory was divided into three judicial districts, and a district court was established in each district. Each of the Supreme Court justices were assigned to one of the district courts and served as district court judge. This arrangement certainly made some litigants uneasy, as a member of the Supreme Court would be reviewing the very decisions he made as a district court judge. The district courts were courts of general jurisdiction, dealing with all matters that were outside the jurisdiction of the justice of the peace courts.

The justice of the peace courts were established to deal with controversies in which less than $100 was at stake. Further, the justice of the peace courts could not determine controversies that involved the title or boundaries of land. The territory’s justice of the peace court made history when Esther Hobart Morris was appointed as the country’s first female justice of the peace. She was sworn in on February 14, 1870, in South Pass City in Sweetwater County, and served until December 6, 1870.

The final court established by the Organic Act is the probate court. The Organic Act focused primarily on the functions of the other three courts and gave very little specificity in terms of the purpose and duties of the probate court. Probate judges also served as the county treasurer.

Once Wyoming became a state, its court system was established by Article V of the Wyoming Constitution. The Constitution originally established four courts: courts of arbitration; justice of the peace courts; district courts; and the Supreme Court. However, through various constitutional amendments and legislation, the character of each of the courts changed, some courts were added, while others were completely abolished.

Regarding the Wyoming Supreme Court, the Constitution afforded the Supreme Court appellate jurisdiction over the district courts and original jurisdiction in matters of extraordinary relief. There were three justices on the Court, and the justices were elected by the voters of the state for eight-year terms. If a vacancy occurred during the middle of a term, the governor appointed a replacement to finish the term. The Constitution also mandated which justice would serve as chief justice by how much time was left to serve in the eight-year term before the next election. Importantly, the Constitution established that the Supreme Court was separate and independent from the district courts. This was a matter of significant debate at the constitutional convention. Some people were concerned that the new state did not have the resources of an additional $6,000 to support separate judges for the various courts. However, the concerns of the Supreme Court justices also serving as district court judges in the territorial courts won the debate. Delegate Smith argued: “What is the matter of a few thousand dollars compared with the rights of life and liberty?” Delegate Riner echoed that sentiment: “I have talked with men in Carbon County, in Albany County, and men in Laramie County, and I find that the universal sentiment is very largely in favor of a supreme court, and an independent supreme court, where a man knows when he takes his case into court, he can go there and get full and impartial justice

In 1957, the Wyoming Legislature proposed an amendment to the Constitution that would change the required number of justices on the Court from three to four.

While having an even number of justices seemed counterproductive to always having a majority vote, the voters were informed that the Court would operate in panels of three on cases—similar to the United States Courts of Appeal—and the justices would rotate themselves on the panels. The voters approved the amendment; however, the four justices always sat on every case, resulting in many decisions without a majority vote. In those cases, the decisions of the district courts were affirmed. In 1971, the Wyoming Legislature proposed another amendment to the Constitution that would change the number of justices from four to “not less than three nor more than five justices as may be determined by the legislature.” Currently, there are five justices on the Court. Approved by the voters, the amendment also allowed the members of the Court to determine who would serve as chief justice.

As to the district courts, originally the Constitution divided the state into three judicial districts, but gave the legislature the authority to establish more if needed. However, the Constitution explicitly stated that the legislature could not authorize more than four judicial districts or district court judges until the taxable valuation of property in the state exceeded $100,000,000. At the time of statehood, Laramie, Converse, and Crook counties comprised District One; Albany, Johnson, and Sheridan counties comprised District Two; and Carbon, Sweetwater, Uinta, and Fremont counties comprised District Three. Over time, other counties were created and now the state’s 23 counties make up nine judicial districts and have 27 presiding district court judges.

There also has been an evolution of the arbitration, justice of the peace, county, and circuit courts. The Constitution also originally established courts of arbitration and justice of the peace courts. The Constitution did not say much about the arbitration courts, but it granted the justice of the peace courts jurisdiction over civil cases of up to $200, misdemeanors, and the authority to bind felonies cases over to the district courts. In 1965, the legislature proposed an amendment that would eliminate the justice of the peace and arbitration courts from the Constitution. Thus, the Constitution would establish the judicial power of the state in “a supreme court, district courts, and such subordinate courts as the legislature may, by general law, establish and ordain from time to time.” However, any justice of the peace and arbitration courts that had already been established would stay in existence until the legislature took future action. The voters approved the amendment.

In the late 1970s, the legislature decided to replace justice of the peace courts with county courts. In counties with a population of more than 30,000 residents, the board of county commissioners was required to establish a county court, thus, eliminating the justice of the peace court in that county. However, if the county’s population was less than 30,000 residents, the board of county commissioners had the choice to either transition to a county court or keep the justice of the peace court. County courts had greater jurisdiction than the justice of the peace courts. The county courts had jurisdiction over civil cases of up to $4,000 (later changed to $7,000), small claims, forcible entry and detainers, misdemeanors, and could conduct bail and preliminary hearing for felony cases. Originally, the number and location of county judges were determined by the Board of County Commissioners in each county after consulting with the district court judge located in the county. However, in 1981, the legislature amended the process, and took control over determining the number and location of county judges in each county.

Because of the differences in how county courts and justice of the peace courts functioned, the legislature decided to replace both county courts and justice of the peace courts with the circuit courts. In 2000, the legislature passed the Court Consolidation Act which transitioned all counties into the circuit court system. The legislature determined how many circuit court judges would sit in each district, and the judges serve for four-year terms. The circuit courts have a similar jurisdiction to what the county courts had, but the circuit courts also exercise jurisdiction over liens and abandoned vehicle disposals. In 2011, the legislature increased the circuit courts’ civil jurisdiction over matters of up to $50,000.

With respect to juvenile and domestic relations court, in 1947, the legislature proposed a constitutional amendment that would give the legislature the authority to establish these specific courts. The amendment passed, but the legislature did not exercise any authority under the amendment until 1971. At that time, the legislature passed the Juvenile Court Act of 1971, which established a statewide county based system of juvenile courts. The juvenile courts are staffed by district court judges and have general jurisdiction over minors alleged to be delinquent, neglected, or in need of supervision. The legislature has never acted on its authority to establish domestic relations courts.

Turning to the appointment and terms of judges, at statehood, the Constitution did not put limits on how long a justice or judge could serve so long as he or she continued to be chosen by the voters. However, significant changes to the judicial selection process, how long a justice or judge can serve, and the supervision of the Judicial Branch was proposed by the legislature in 1971.

First, the legislature sought and the voters approved an amendment to the Constitution establishing a Judicial Nominating Commission dramatically changing the judicial selection process. Instead of justices and judges being elected by the voters, a Judicial Nominating Commission interviews candidates and narrows that pool down to three individuals. The names of those three individuals are given to the governor, who then must choose one of the three to fill the judicial vacancy. The commission consists of the chief justice, three attorneys selected by members of the state bar association, and three lay members appointed by the governor. This merit based process, however, recognizes the importance of the voters having input into the process, so instead of partisan elections, the justices and judges stand for retention. Supreme Court justices must stand for retention every eight years, district court judges every six, and circuit court judges every four. The non-partisan, retention elections are a simple “yes” or “no” answer of whether the voter believes the justice or judge should be retained in office.

Second, the amendment mandates that a justice or judge must retire when he or she reaches the age of 70.

Finally, the amendment created the Judicial Supervisory Commission. The commission considers complaints of judicial misconduct made against judicial officers and may propose discipline of a judicial officer to the Supreme Court. After a hearing, the commission may recommend retirement, censure, or removal from office due to issues surrounding performance or misconduct. In the mid-1990s voters approved an amendment to change the name to the Commission on Judicial Conduct and Ethics. The commission consists of 12 members: three active judges who are not on the Supreme Court; three members of the state bar; and six electors of the state who are not judges or attorneys and are appointed by the governor.

Thanks again for your interest in Wyoming’s Judiciary. In closing, here are a few fun and noteworthy facts:

- In 2000, Marilyn Kite was the first woman appointed to the Wyoming Supreme Court. She served as chief justice from 2010-2014 and retired from the Court in 2015.

- Willis Van Devanter, who served as the chief justice of the territory’s Supreme Court, was appointed by President William Taft to the United States Supreme Court.

- Fred H. Blume has the distinction of being the longest serving justice on the Wyoming Supreme Court. He became a member of the Court in 1921 and retired in 1963, serving the Court for 42 years.